The 2016 Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) reports a continuing and increasing acceleration of the security trends observed in previous assessments. The additional increase in volume, scope and financial damage combined with the asymmetric risk that characterises cybercrime has reached such a level that in some EU countries cybercrime may have surpassed traditional crime in terms of reporting1,2. Some attacks, such as ransomware, which the previous report attributed to an increase in the aggressiveness of cybercrime, have become the norm, overshadowing traditional malware threats such as banking Trojans.

The mature Crime-as-a-Service model underpinning cybercrime continues to provide tools and services across the entire spectrum of cyber criminality, from entry-level to top-tier players, and any other seekers, including parties with other motivations such as terrorists. The boundaries between cybercriminals, Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) style actors and other groups continue to blur. While the extent to which extremist groups currently use cyber techniques to conduct attacks appears to be limited, the availability of cybercrime tools and services, and illicit commodities such as firearms on the Darknet, provide ample opportunities for this situation to change3.

Many of the key threats remain largely unchanged from the previous report. Ransomware and banking Trojans remain top malware threats; a trend unlikely to change for the foreseeable future. While the same data stealing malware largely appears year-on-year, ransomware – a comparatively more recent threat – is in greater flux and may take several more years before it reaches the same level of equilibrium.

Peer-to-peer networks and the growing number of forums on the Darknet continue to facilitate the exchange of child sexual exploitation material (CSEM); while both self-generated indecent material (SGIM) and content derived from the growing phenomenon of live-distant child abuse, further contribute to the volume of CSEM available.

EMV (chip and PIN), geoblocking and other industry measures continue to erode card-present fraud within the EU, forcing criminals to migrate cash out operations to other regions. Logical and malware attacks directly against ATMs continue to evolve and proliferate. The proportion of card fraud attributed to card-not-present (CNP) transactions continues to grow, with e-commerce, airline tickets, car rentals and accommodation representing the industries hit hardest. The first indications that organised crime groups (OCGs) are starting to manipulate or compromise payments involving contactless (NFC) cards have also been seen.

The overall quality and authenticity of phishing campaigns has increased, with targeted (spear) phishing aimed at high value targets - including CEO fraud - reported as a key threat by law enforcement and the private sector alike.

DDoS attacks continue to grow in intensity and complexity, with many attacks blending network and application layer attacks. Booters/stressers4 are readily available as-a-service, accounting for an increasing number of DDoS attacks. While other network attacks aimed at exfiltrating data continue to focus on financial credentials, there is a growing trend in the compromise of other data types, such as medical5 or other sensitive data or intellectual property for other purposes.

Cryptocurrencies, specifically Bitcoin, remain the currency of choice for much of cybercrime, whether they are used as payment for criminal services or for receiving payments from extortion victims. Even so, key members of the Bitcoin community, such as exchangers, are increasingly finding themselves the victim of cybercriminals.

The growing misuse of legitimate anonymity and encryption services and tools for illegal purposes poses a critical impediment and serious threat to the detection, investigation and prosecution of criminals across all crime areas. For law enforcement in particular, this creates a dichotomy of value. Strong encryption is highly important to e-commerce and other cyberspace activity, but adequate security depends on police having the ability to investigate criminal activity.

This report highlights some areas of innovation within the cybercriminal community, but also how much of cybercrime exploits well-known, and in some cases decade-old, techniques and vulnerabilities. Some historic attack vectors, such as malicious Microsoft Office macros6, have come full circle and are once more increasingly popular among cybercriminals.

It should be noted that the majority of reported attacks are neither sophisticated nor advanced. While it is true that in some areas cybercriminals demonstrate a high degree of sophistication in the tools, tactics and processes they employ, many forms of attack work because of a lack of digital hygiene, a lack of security by design and a lack of user awareness.

Nevertheless, a variety of new and innovative modi operandi have been discovered, combining existing approaches, exploiting new technology or identifying new targets. The proliferation and evolution of malware attacks directly against ATMs, indications of compromised payments involving contactless (NFC) cards and the recent attacks against the SWIFT system are examples of this development.

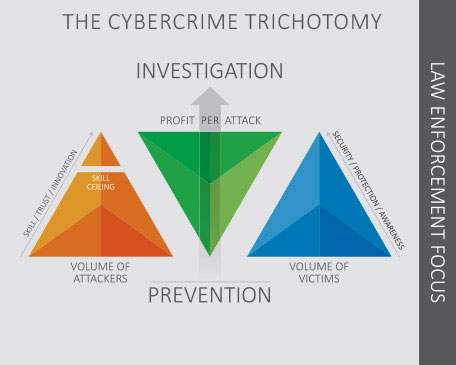

Using the Cybercrime Trichotomy introduced in last year’s report, it is proposed to put an even stronger focus on awareness and prevention when it comes to high volume crimes that can be effectively stopped by increasing the general level of cybersecurity. This should be done in close cooperation at EU level and via public-private partnerships (PPPs). Moreover, law enforcement, together with all relevant partners, needs to step up efforts to demonstrate that criminal behaviour online is met with real consequences. This should involve a stronger focus on and prioritisation of investigation and improved attribution in relation to key criminal actors, tools and services, as well as identifying preventive actions and working proactively with young individuals who may be at risk of conducting criminal activity online7.

The networking model employed by Europol’s EC3 continues to provide tangible results in the fight against cybercrime at EU level and beyond. In the last year the number of successful high-level operations supported by the EC3 (which rose from 72 operations during 2014, to 131 in 2015), with EU and non-EU law enforcement and judicial partners, as well as partners in industry, the financial sector, the CERT community and academia, demonstrate the power of the network.

However, law enforcement, policy makers, legislators, academia and training providers need to become even more adaptive and agile in addressing the phenomenon. Existing frameworks, programmes and tools are often too slow and bureaucratic to allow for a timely and effective response. Rather than multiple partners investing in and developing the same highly specialised skill-sets and expertise, perhaps a more effective, high-level model would be for law enforcement and relevant partners to focus on distinct core competencies and to make them available to others ‘as a service’.

In addition to leveraging existing networks further, EC3, and law enforcement in general, need the resources required to not only maintain but further increase response capacities to keep up with the expanding cybercrime threat within the EU and beyond. This should include the necessary resources to recruit and retain law enforcement personnel with the specialised skills, knowledge and expertise required to examine, analyse and investigate cybercrime as well as to develop or acquire special purpose tools for digital forensics, Big Data analytics and Blockchain investigations.

In order to minimise unnecessary overlap and duplication of efforts by connecting existing initiatives and partnerships, the development of a ‘cyber-security ecosystem’ is needed at EU level and beyond to identify all the relevant partners and stakeholders, map out networks, identify interfaces and links to legal and regulatory frameworks, facilitate easier capacity building and visualise opportunities for the further strengthening of cyber security in the EU. This should include organisations such as EC3, INTERPOL, Eurojust, ENISA, CERT-EU, CEPOL, the International Cyber Crime Coordination Cell (IC4), the National Cyber-Forensics and Training Alliance (NCFTA) and the Cyber Defence Alliance (CDA), to mention some.

It is important to consider law enforcement as one of the key partners in ensuring cybersecurity in the EU. An important aspect in this regard is the systematic and official involvement of law enforcement in cooperation with EU agencies such as ENISA and CERT-EU as well as national/governmental Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) on law enforcement relevant aspects of cyber security. Law enforcement can provide investigative support and valuable information on the methodologies and groups behind cyber attacks.

In the context of the Network and Information Systems (NIS) Directive, law enforcement should be fully engaged, given that the investigation and prosecution of cybercrime is essential for the kind of cross-domain and sector cooperation that is required to effectively and efficiently address cyber threats.