Migrant smuggling has emerged as a highly profitable and widespread criminal activity for organised crime in the EU. The migrant smuggling business is now a large, profitable and sophisticated criminal market, comparable to the European drug markets.

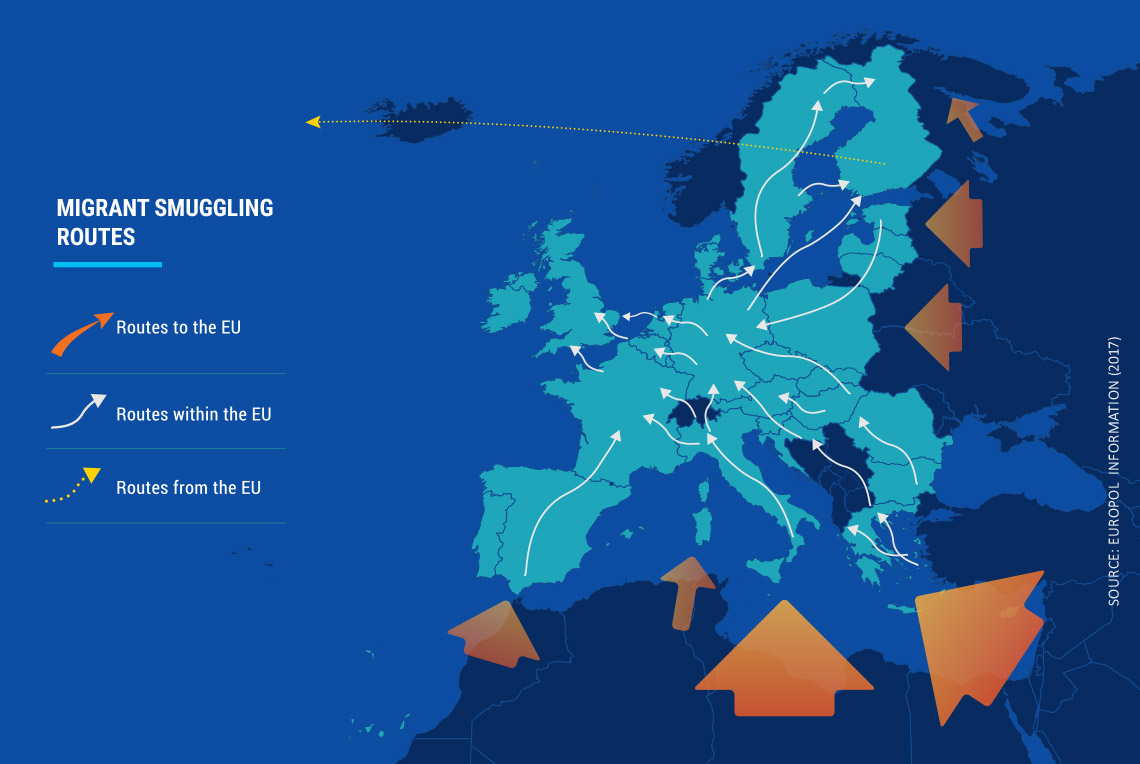

The demand for and supply of smuggling services has grown significantly since 2014. More than 510,000 illegal border crossings between border-crossing points at the external border of the EU were registered in 2016. 29 This is a substantial decrease compared to 2015, when over one million irregular migrants entered the EU on the Eastern Mediterranean and Central Mediterranean routes. 30 Nearly all of the irregular migrants arriving in the EU along these routes use the services offered by criminal networks at some point during their journeys.

During 2016, 1,234,558 applications for asylum were recorded in the EU. In 2015, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) reported just over 295,000 positive decisions on asylum applications by Member States. 31 This means that a large number of irregular migrants who did not apply for asylum or whose applications were rejected may attempt to stay illegally in the EU.

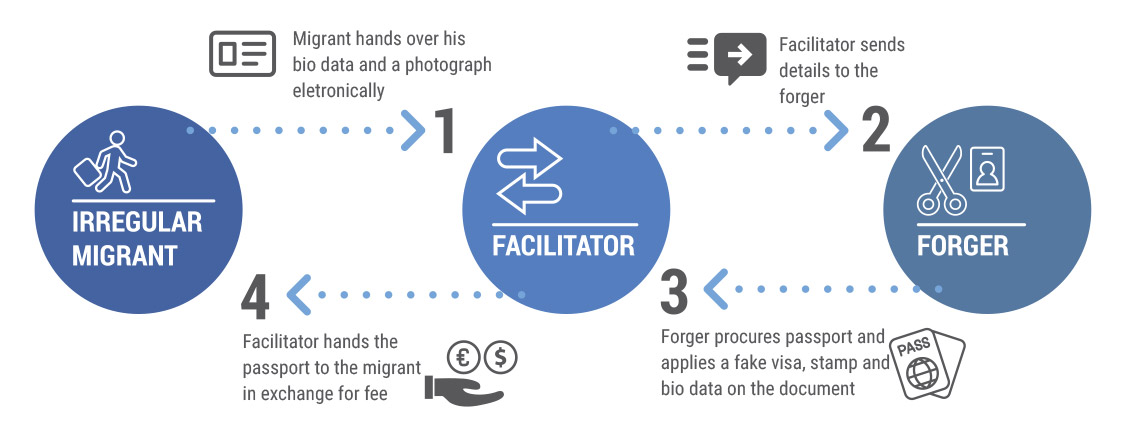

In addition to the transportation of migrants, document fraud has emerged as a key criminal activity linked to the migration crisis. The provision of fraudulent documents will continue to represent a substantial threat to the security of the EU. Fraudulent documents are used and can be re-used for many different criminal offences.

In 2015, migrant smuggling networks offering facilitation services to reach or move within the EU generated an estimated EUR 4.7 billion to EUR 5.7 billion in profit. These profits have seen a sharp decline in 2016, dropping by nearly EUR 2 billion between 2015 and 2016. This development is in line with the overall decrease in the number of irregular migrants arriving in the EU and as a result of a fall in the prices for migrant smuggling services following the peak of the migration crisis in 2015.

OCGs involved in migrant smuggling display an unprecedented level of organisation and coordination. While established smuggling modi operandi remain unchanged, migrant smugglers have shown great versatility in the means of transport, concealment methods and technologies they use.

Migrant smuggling is a multi-national business. Migrant smugglers originating from over 122 countries are involved in facilitating the journeys of irregular migrants to the EU. Most migrant smuggling networks are composed of various nationalities involving both EU and non-EU nationals.

Migrant smuggling networks heavily rely on social media to advertise smuggling services. Migrant smugglers make use of ride-sharing applications and P2P accommodation platforms to provide a cover for their smuggling activities. This leaves regular users at the risk of inadvertently becoming facilitators by unknowingly transporting or hosting irregular migrants.

Migrant smuggling is a highly profitable criminal activity featuring sustained high levels of demand and relatively low levels of risk. Some OCGs previously involved in other criminal activities such as the illegal trade in excise goods, drug trafficking or organised property crime have added migrant smuggling to their portfolio of criminal activities. Migrant smuggling does not require access to significant resources and OCGs can rely on their existing knowledge of routes and infrastructure used to smuggle goods across borders. The distinction between legal and illegal activities is increasingly blurred. Individual criminal entrepreneurs can step in and out of criminal activities by providing ad hoc services, especially taxi and truck drivers.

OPERATION DAIDALOS

In March 2015, Operation Daidalos targeted a criminal group smuggling irregular migrants from Greece to other Member States which was involved in the production and distribution of forged travel documents. In addition to providing these documents to irregular migrants, the group also sold these to other OCGs. The criminal network operated primarily in Greece.

Service packages offered by migrant smugglers now frequently include the provision of fraudulent travel and identity documents. Fraudulent documents allow irregular migrants to enter and move within the EU as well as to change from irregular to legalised residence status under false pretences or by using fake identities. Migrant smuggling networks are increasingly offering tailor-made facilitation services including high-quality fraudulent documents.

The abuse of genuine passports by look-alikes continues to be the main modus operandi used by document fraudsters. ID cards are the most commonly detected document used as part of document fraud. In 2015, they accounted for 50% of all detections in the EU. In 2016, more than 7,000 people were detected with fraudulent documents on entry at the external borders of the EU. 32

Both the quantity and the quality of fraudulent documents circulating in the EU have increased. The sustained increase in demand for fraudulent documents has prompted established counterfeiters to increase their production output and establish new print shops.

Migrant smugglers frequently abuse legal channels to facilitate the entry of irregular migrants to the EU or to legalise their stay. The abuse of legal channels involves a variety of modi operandi including sham marriages, bogus paternity, false employment contracts, fake invitation letters, false medical visas, and false claims of being victims of trafficking or refugees.

Migrant smuggling networks offer their services including transportation, accommodation, the provision of fraudulent documents and information on contact points in other countries.

Migrant smugglers pass irregular migrants from one network to another along the route of the migrants’ journey.

EU suspects typically work as drivers transporting irregular migrants within the EU to destination countries.

Migrant smugglers widely rely on social media and use online platforms such as ride-sharing websites, or P2P accommodation platforms, to arrange facilitation services.

Document fraud has emerged as a key criminal activity linked to the migration crisis.

THB for sexual and labour exploitation includes the recruitment, transportation, harbouring and exploitation of victims. OCGs involved in THB typically operate in independent cells that deal with the various stages of recruitment, transport and exploitation.

Traffickers rely heavily on document fraud to enable their trafficking activities. This includes the use of fraudulent identity, travel and breeder documents as well as the abuse of legal channels such as the EU visa regime for tourism, study and work visas. OCGs involved in THB also continue to exploit asylum provisions in order to traffic non-EU nationals into the EU. On many occasions, victims are provided with fraudulent documents to conceal their real identity and age.

The sexual exploitation of EU nationals no longer relies predominantly on the use of violence and coercion towards victims. Some OCGs are increasingly relying on threats of violence towards victims and their families rather than attacking the victim. Victims originating from outside the EU are still routinely subjected to violence, debt bondage, passport confiscation and other forms of coercion as an integral part of trafficking modi operandi.

The involvement of OCGs in THB for labour exploitation is increasing in the EU. OCGs cater to the growing demand for cheap labour across many Member States and have access to a large number of potential victims. THB for labour exploitation threatens to infiltrate the legal economy, where it lowers wages and hampers economic growth.

THE BUSINESS MODEL

There has been little change in the types of industries featuring labour exploitation. Traffickers continue to target less regulated industries as well as those featuring seasonal demand for workers. Vulnerable sectors include agriculture, catering, cleaning, construction, entertainment, fishing, hospitality, retail and transportation.

Traffickers take advantage of discrepancies in labour legislation to organise the exploitation of victims in the grey zone between legal employment and labour exploitation. Some victims receive wages equivalent to the minimum standard in their countries of origin.

However, these are far below acceptable salaries in countries of exploitation where they do not have sufficient resources to cover their living expenses. These wage dumping practices seriously undermine the legal labour market in countries of destination and make it difficult for victims of labour exploitation to be recognised as such.

CRIMINAL GANG ACCUSED OF TRAFFICKING OVER 150 WOMEN INTO PROSTITUTION DISMANTLED BY AUSTRIA 33

In November 2016, Austrian law enforcement authorities with the support of Europol dismantled a Chinese OCG involved in the trafficking of up to 300 women. Victims were lured to Austria on promises of work as nannies or masseuses. They were provided with forged documents and brought to Austria illegally. Upon their arrival in Vienna, OCG members took away the victims’ IDs. The women were placed in so-called “sex studios” owned by the OCG and forced to work as prostitutes. After a few weeks they were transferred to other brothels in Austria.

Traffickers often specifically target underage victims, both male and female, to sexually exploit them. The exploitation of underage victims is not always motivated by financial profit. In some cases, underage victims are trafficked for the purpose of producing CSEM, which is traded on online platforms.

TRAFFICKING VICTIMS FORCED INTO CRIMINALITY 34

In November 2016, a Spanish investigation supported by Europol resulted in the arrest of 16 suspected traffickers and the rescue of nine minors. The OCG trafficked young women and forced them into pickpocketing in various Member States. The victims were initially lured to Spain and travelled there using counterfeit documents. In Spain, the traffickers trained the victims in pickpocketing techniques and forced them to commit thefts in crowded areas and on public transport. The OCG shared family ties and was hierarchically structured operating in smaller groups in different European cities. The larger criminal network was mainly composed of nationals from Bosnia and Herzegovina and traded the victims from one group to another for an estimated EUR 5,000 each.

THB for labour exploitation is

increasing in the EU.

THB for labour exploitation is

increasing in the EU.

Traffickers continue to target less regulated industries as well as those featuring seasonal demand for workers.

The traditional trafficking flow from Eastern Europe to Western Europe has been replaced by multiple and diverse flows of victims all over the EU.

OCGs have further increased

the use of legal businesses that can conceal exploitations such as hotels, nightclubs and massage parlours.

OCGs have further increased

the use of legal businesses that can conceal exploitations such as hotels, nightclubs and massage parlours.

Traffickers often specifically target underage victims, both male and female, to sexually exploit them.

Traffickers continue to rely on the use of social media, Voice-over-IP (VoIP) and instant messaging applications at all stages of the trafficking cycle.

OCGs involved in THB often exploit existing migratory routes to traffic victims within the EU. While the migration crisis has not yet had a widespread impact on THB for labour exploitation in the EU, some investigations show that traffickers are increasingly targeting irregular migrants and asylum seekers in the EU for exploitation. Irregular migrants in the EU represent a large pool of potential victims susceptible to promises of work even if this entails exploitation.

SHAM MARRIAGES

There has been an increasing number of reports of incidents of sham marriages in several Member States. This increase is likely related to the migration crisis and an increase in the number of irregular migrants seeking to transition to legal residence status after failed asylum applications.

MIGRANT SMUGGLING AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING RING OPERATING VIA THE MEDITERRANEAN 35

In November 2015, a joint operation between Spanish and Polish law enforcement authorities, coordinated by Europol, revealed the operation of a migrant smuggling network exploiting irregular migrants from Pakistan in restaurants in Spain. Irregular migrants were forced to work long hours in appalling conditions without salary, holiday or social security to repay their debts to smugglers for the travel and provision of fraudulent documents. The migrant smugglers used the criminal proceeds to invest in new restaurants, which were also used for the exploitation of irregular migrants.