EU citizens kidnapped or killed

Terrorist and armed criminal groups continue to consider citizens of the EU and other western countries as highvalue targets for kidnapping. This is because ransom money is a significant source of revenue for some groups; the extensive media attention attracted by western hostages can be exploited for propaganda and political pressure; and hostages can be used in prisoner swaps. It is assessed that militant groups do not select individuals of specific nationalities but target their victims opportunistically.

The total number of abducted EU citizens is difficult to estimate due to the fact that not all the kidnapping incidents are reported for reasons related to the security of the hostages. In 2016, the kidnap threat remained very high in and around conflict zones, as well as in areas with little or no governmental control. Incidents involving the kidnapping of westerners occurred in Libya, Mali, Afghanistan and the Philippines. In addition, Syria, Iraq and Yemen remained high-risk countries, although no abductions were reported in their territories in 2016.

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has been very active the regions of Maghreb and the Sahel. In January, AQIM militants abducted a Swiss female missionary in Timbuktu (Mali). Shortly after, the group posted a video online demanding, inter alia, the release of its fighters held in Malian prisons, as well as of a member of Ansar Dine (supporters of the religion), who was at that time standing trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. A second video was released in June as proof of life. The hostage was still in the hands of AQIM at the time of writing. AQIM also continued to hold a British–South African and a Swedish hostage, who were kidnapped from a restaurant in Timbuktu in November 2011.

In the same region, a Romanian citizen that was abducted in April 2015 in the border area between Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, remained in the hands of his captors in 2016. The kidnapping was claimed, in May 2015, by a faction of al-Murabitun, which at the same time pledged allegiance to IS. In October 2016, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), with which the rest of al-Murabitun had merged in late 2015, posted a video statement online, said to have been recorded in late September, in which the hostage stated that he was in good health and pleaded to the Romanian government to do everything for his release. The release of the video by AQIM coincided with the faction responsible for the kidnapping reiterating its pledge to IS. Thus, the hostage seems to have become an object of dispute in the conflict between IS and al-Qaeda in the region. Romania reported that the Burkina Faso government did not receive a request for ransom.

In Libya, IS and other militant groups continued to take advantage of the instability of the country and carried on with their terrorist and criminal activities. In March 2016, two Italian employees of a construction company were killed in the area of Sabratha, during a fight between Libyan security forces and their captors. They had been abducted by IS in July 2015 near the towns of Zwara and Mellitah, along with two other Italians who were held in a different location and managed to escape, also in March 2016. IS militants still hold an Austrian and a Czech national, who were abducted in March 2015 from an oilfield in Zalla, along with seven more people from Ghana and the Philippines. In Ghat, south-western Libya, a local armed group kidnapped two Italian employees of a construction company in September 2016 and released them in November. No details regarding their abduction or release have been disclosed.

In the Philippines, the terrorist group Abu Sayyaf continued to carry out kidnappings. In April, its members killed a British–Canadian and in June a Canadian hostage. Both men had been abducted in September 2015, along with a Norwegian and a Filipino, from a resort in the southern Philippines. The Norwegian man remained captive at the time of writing, whereas the Filipino was released in June 2016. Abu Sayyaf militants were also behind the kidnapping of a German man and the murder of his wife while they were sailing off the southern Filipino coast in November. They demanded a ransom of PHP 30 million (EUR 565 000) but consequently killed the hostage. In February 2017, a video was posted online that appeared to show the execution. An Italian citizen abducted by Abu Sayyaf militants in October 2015 in the city of Dipolog was released in April 2016. The hostage was held on the island of Jolo, the stronghold of the terrorist group, where he spent his captivity with other hostages.

In Syria in May, Jabhat Fath al-Sham (former Jabhat al-Nusra) released three Spanish journalists that were abducted near Aleppo in July 2015. The group also claimed it freed a German woman and her baby in September 2016, denying it was responsible for her kidnapping. The woman had been abducted in October 2015. These releases are assessed to be part of the group’s attempts to distance itself from IS practices.

A British journalist held hostage by IS since November 2012 continued to appear in propaganda material. He featured in two IS videos released in December 2016.

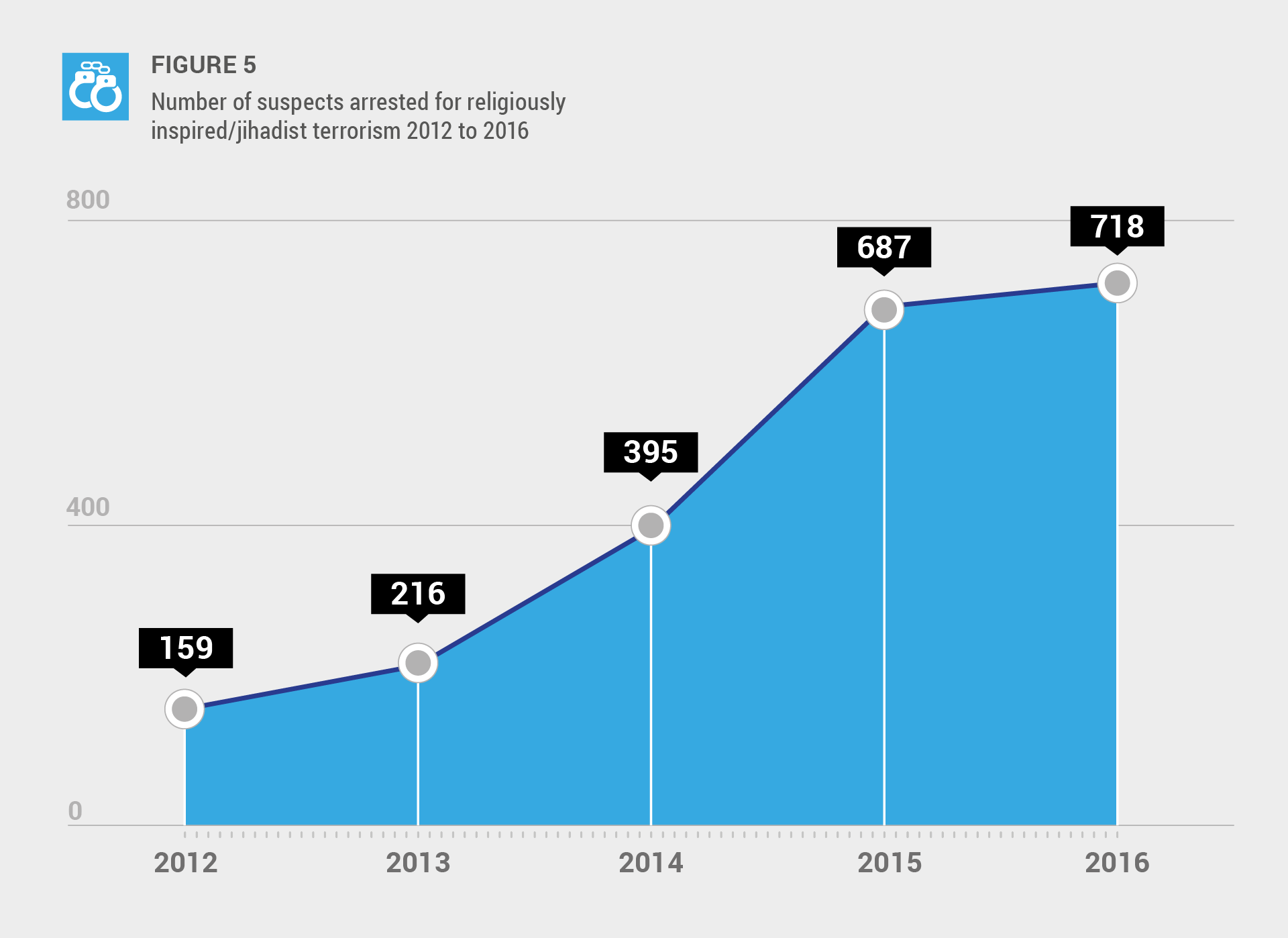

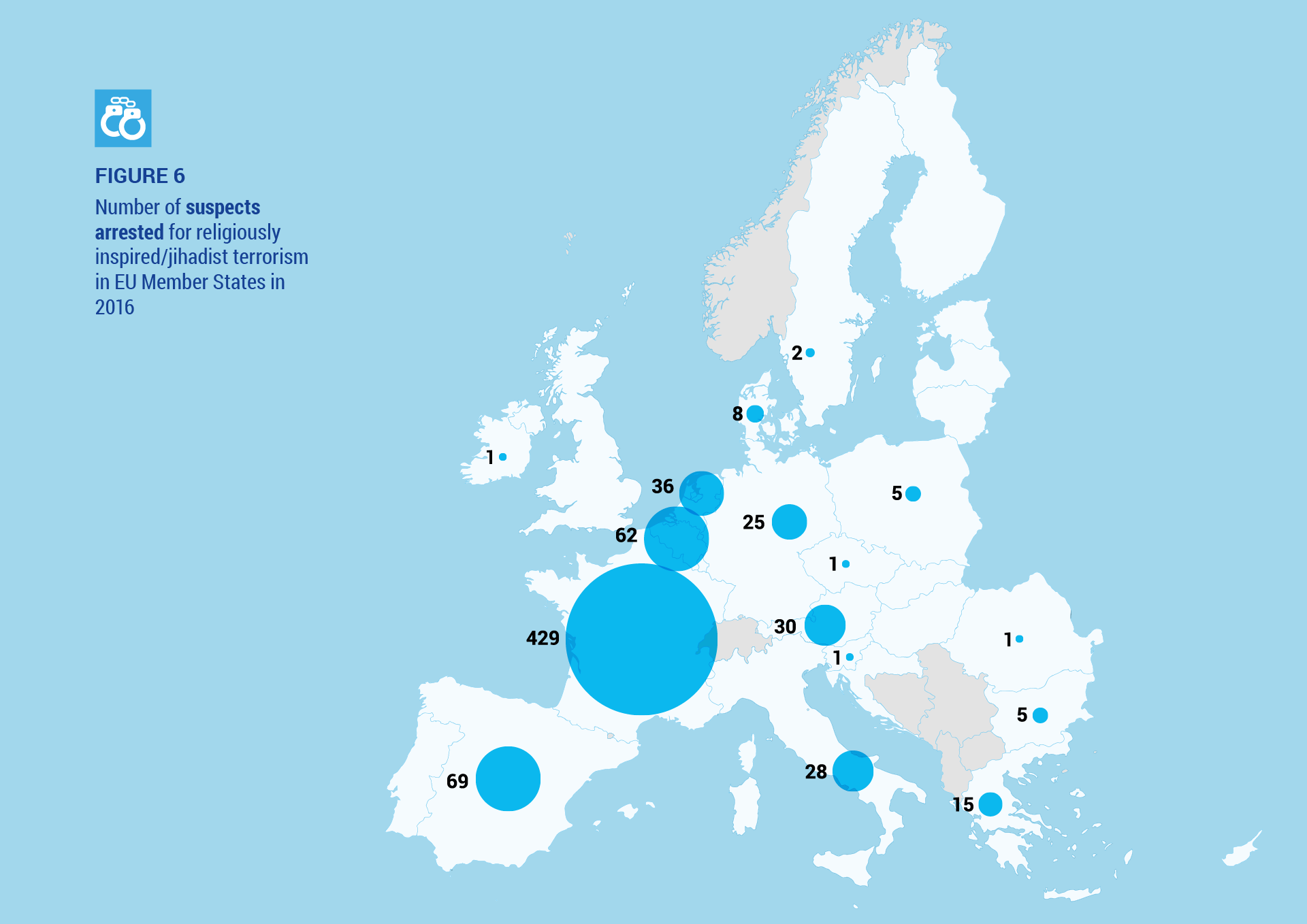

people arrested on suspicion of jihadist terrorism related offence

people arrested on suspicion of jihadist terrorism related offence